Equity, excellence, opportunity to learn, and social justice are at the heart of everything we do at MAEC. Over the past 25 years, we have operated many projects directed towards these goals. We are the long-time home of a regional technical assistance center funded by the U.S. Department of Education. The federal equity assistance centers were created to serve state departments of education, districts, and schools and help them address issues relating to race, gender, religion, and national origin (English Learners). As of 2016, MAEC’s region now encompasses 15 states and territories. Designated as Region I, the Center for Education Equity (CEE) at MAEC reaches Connecticut, Delaware, Kentucky, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, Puerto Rico, Rhode Island, Vermont, Virgin Islands, and West Virginia. MAEC also supports the Region II equity assistance center which stretches across the South.

We strongly believe that every student matters and should be afforded the opportunities, resources, and supports necessary to succeed. To achieve educational equity, efforts must be intentional, accountable, and contextual. This goal requires an examination of systemic policies and practices, school climate, student access to support for rigorous curriculum, and teaching and learning. MAEC facilitates this process by reviewing the cultural, structural, and material dimensions necessary for making transformational change. We provide technical assistance, professional learning, and tools necessary to operationalize equity into practice.

Community Resource Mapping – Educational Equity

MAEC uses a strengths-based approach for asset mapping, since often the best solutions come from within the communities in which our districts/schools reside. These key stakeholders include districts, schools, communities, and families all who are seeking to increase student achievement. To this end, MAEC conducts community walks and community resource mapping to identify potential partners and allies for effective and efficient delivery of services. This process includes attention to alignment between district and school needs and priorities so together partners can build the social and human capital that will help students and staff thrive.

Comprehensive Needs Assessment – Educational Equity

Beginning with a disaggregated data analysis of student achievement, student discipline, and school climate, MAEC is able to effectively determine client strengths and areas of need. This collaborative inquiry approach enables MAEC to examine multiple sources of data. Using a culturally responsive and equity framework, further creates opportunities to develop operational action plans to tackle complex challenges that pose barriers to gains in student achievement.

Culturally Responsive Family, School, and Community Engagement – Educational Equity

A family is a child’s first teacher. When families’ partner with schools and community organizations, children thrive. To produce the best results for students, MAEC builds the capacity of families, educators, schools, and community organizations to collaborate, exchange ideas, and develop and implement policies and action plans. We build on the collaborative strengths of families, educators, and community members so they can each contribute to the development and success of diverse students.

Culturally Responsive Leadership – Educational Equity

Leaders set the tone and expectations of any organization. They do this by responding effectively to the diverse communities that they serve, being asset-focused, and proactive problem solvers. Culturally responsive leadership technical assistance provides a multi-dimensional framework that builds capacity of educators who are culturally informed and highly skilled in culturally responsive practice.

Advancing Capacity as Culturally Proficient Leaders

This training series is designed to advance the capacity of district leadership to embed cultural proficiency into their roles as they support staff. MAEC collaborates with clients to examine the systemic and structural roles of cultural proficiency in school district transformation. The trainings include the following components: Cultural Proficiency Continuum, School Leader Identity Reflection, Multicultural Education – Cultural Influence on Perspective, Multiple Worlds Theory, Historical, Societal, and Political Contextualization, Cultural Responsive Leadership Norms, Essential Elements of Cultural Proficiency, Building Positive School Culture and Climate, and Culture and Climate Self Study.

Culturally Responsive Discipline Models and Practice

Creating a positive school and classroom culture is essential to reducing disruptive behaviors that lead to referrals and suspensions. Culturally Responsive Discipline Models and Practice guides educators through the exploration and analysis of discipline models, continuum of interventions and supports, and the creation of equity centered student codes of conduct. The trainings include the following components: School Climate and Culture, PBIS vs. CRPBIS, School Climate Survey Samples, Student Codes of Conduct Models, Root Cause Analysis, and Reducing Disproportionality.

Culturally Responsive Teaching and Learning

This series of training is intended for school-based educators to explore the impact that identity and context have on teaching and learning; build an understanding of educational access, participation, and outcomes as they relate to issues of power and privilege; and apply new knowledge to begin planning for culturally responsive practice implementation. The trainings include the following components: Opportunity Gaps, Disproportionality, Exploring Personal Identity, Perceptions about Students and Learning, Structural Racism vs. Poverty, Cultural Context, Data Analysis and Decision-Making, and Asset-based Approach to Teaching and Learning.

Ensuring Educational Equity for English Learners

Under Title VI and Title III of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, school districts are prohibited from discriminating on the basis of race, color, and national origin. This training highlights the requirements surrounding the provision of services for ELs with an emphasis on the identification, placement, provision of alternative program for ELs, access to challenging content, and assessment. In addition, the training addresses the legal rights of parents/guardians.

Evolving as Culturally Responsive Educators

This training series is intended to advance participants’ growth as culturally competent educators and leaders. The trainings include the following components: Cultural Proficiency Continuum, School Educator Identity Reflection, Cultural Influence on Perspective, Habits of Mind, Elements of Cultural Identity, Essential Elements of Cultural Proficiency, and Multicultural Education – Cultural Influence on Perspective.

Title IX , Anti-Bullying and Sexual Harassment Compliance for School Districts and Schools

This training provides an overview of Title IX requirements and will prepare participants to respond to incidents of harassment and bullying with proactive, timely, and culturally responsive practices, ensuring employee and students’ rights.

CEE Supports Falmouth Public Schools in Advancing Equity and Inclusion

In 2023, the Center for Education Equity (CEE) at MAEC, Region I Equity Assistance Center, collaborated with Falmouth Public Schools (FPS) to advance district-wide initiatives focused on diversity, equity, inclusion, and belonging (DEIB). This partnership aimed to address systemic disparities and promote equitable educational environments. CEE’s support included leading a comprehensive equity needs assessment, utilizing the MAEC Equity Audit Tool to examine key areas such as:

- District policies and practices

- School climate and community engagement

- Curriculum development and disciplinary procedures

Helping English Learners Achieve the Common Core in Delaware, District of Columbia, and West Virginia

The Mid-Atlantic Equity Center has partnered with the Mid-Atlantic Comprehensive Center at WestEd to co-host a Title III State Coordinators Community of Practice to increase English Learner achievement in the Common Core State Standards. The purpose of the convening is to provide Title III State Coordinators with:

- A professional network of job-alikes across the region to share best practices, research, and tools to improve the delivery of services to local education agencies to serve English Learners and their families;

- Increased capacity to provide technical assistance to local education agencies in establishing cooperative and collaborative coaching opportunities between general content teachers and ESOL teachers; and

- Professional learning opportunities provided by leading national and regional experts on English Language Acquisition, Academic Language Development, and Co-Teaching Models for General Education/ESOL Teachers.

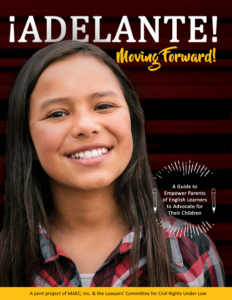

¡Adelante! Moving Forward!

¡Adelante! Moving Forward!

A Guide to Empower Parents of English Learners to Advocate for their Children

In 2010, approximately five million students in the United States were identified as English Learners (ELs). Students under this category have different English proficiency levels and years of formal education. Schools must be able to support students of different backgrounds and proficiency levels equally and ensure access to quality education for academic success as they continue to learn English.

There is a substantial body of legislation, the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA), which protects the rights of these students. Unfortunately, many families of ELs are unaware of these laws and thus cannot advocate for their children. ¡Adelante! Moving Forward! A Guide to Empower Parents of English Learners to Advocate for their Children is designed as an informational training tool to provide trainers of immigrant families and family leaders with user-friendly and accessible information regarding the legal responsibilities of educational agencies serving ELs and the rights of families of ELs.

The publication was developed through a partnership between the MAEC and the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law’s Parental Readiness and Empowerment Program (PREP). It is available in English and Spanish.

In 2010, approximately five million students in the United States were identified as English Learners (ELs). Students under this category have different English proficiency levels and years of formal education. Schools must be able to support students of different backgrounds and proficiency levels equally and ensure access to quality education for academic success as they continue to learn English.

There is a substantial body of legislation, the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA), which protects the rights of these students. Unfortunately, many families of ELs are unaware of these laws and thus cannot advocate for their children. ¡Adelante! Moving Forward! A Guide to Empower Parents of English Learners to Advocate for their Children is designed as an informational training tool to provide trainers of immigrant families and family leaders with user-friendly and accessible information regarding the legal responsibilities of educational agencies serving ELs and the rights of families of ELs.

The publication was developed through a partnership between the MAEC and the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law’s Parental Readiness and Empowerment Program (PREP). It is available in English and Spanish.

Advancing Equity through STEM Education

Advancing Equity through STEM Education

Inspire students to embrace and learn STEM with lessons that increase equity and inclusive instruction. Teachers can improve equity in STEM education by following key principles and features that address the historical marginalization of women and BIPOC communities and reframe traditional instructional practices to be more inclusive of different ways of learning. Following an Understanding by Design Framework, the guide outlines each principle’s desired learning outcomes and performance indicators and provides suggested learning plans. Each principle’s features detail the issues surrounding STEM education inequities and offer new approaches incorporating culturally responsive teaching, improving classroom climates, and applying real-world examples. Advancing Equity through STEM Education makes the case that equitable teaching can revitalize academic disciplines and help students connect and take ownership of their learning.

Link: https://maec.org/stem-education/

Advancing Racial and Socioeconomic Diversity Playbook: A Guide for Administrators

Advancing Racial and Socioeconomic Diversity Playbook: A Guide for Administrators

While U.S. public education is experiencing an increase in student body size and diversity, there is also an increase in racial and socioeconomic isolation. Participation rates among White students are decreasing as rates among Latine and Asian American and Pacific Islander students increase, and Black student participation rates hold steady. Schools, districts, and communities must be prepared to address these two forms of segregation to ensure equity and success for all students. Advancing Racial & Socioeconomic Diversity Playbook provides a comprehensive integration planning guide with tools to help build inclusive teams, analyze segregation in your district, and refine plans. The planning guide and worksheets offer teams opportunities to review racial and socioeconomic issues side-by-side and together.

Link: https://maec.org/ses_playbook/Arab American Heritage Month Resource List

This Arab American Heritage Month, we celebrate the histories, cultures, and contributions of Arab Americans. We invite you to expand your knowledge and awareness of the experiences and histories of Arab Americans. From lesson plans to movie recommendations, our resource list can help get you started.

Articles

- American-Arab Anti-Discrimination Committee (ADC)

- Arab American Heritage Month 2024 (History.com)

- Celebrating Arab American Heritage Month (Learning for Justice)

- Guide to Observing Arab American Heritage Month (San Diego Office of Education)

- How Teachers Can Support Arab-American Students (Cult of Pedagogy)

- National Arab American Heritage Month (Arab American Foundation)

- Resources for Addressing Religious Discrimination (MAEC)

- “The Story of Arab & Muslim Students Is Often an Untold Story” (EdWeek)

- Supporting Arab American Students in the Classroom (Learning for Justice)

Books

- A Map of Home, by Randa Jarrar

- Arab in America, by Toufic El Rassi

- Conditional Citizens: On Belonging in America, by Laila Lalami

- Crescent Moons and Pointed Minarets: A Muslim Book of Shapes, by Hena Khan and illustrated by Mehrdokht Amini

- The Girl in the Tangerine Scarf, by Mojha Kahf

- Refugee, by Alan Gratz – staff pick, Jenny Portillo

- The Turtle of Oman, by Naomi Shihab Nye

Lesson Plans

- Arab American Heritage Month Resource Guide (TeachMideast-Middle East Policy Council)

- Arab American National Museum Lesson Plans (Arab American National Museum) - note: lesson plans are in the drop-down menu on the right side of the page

- Remembering Mahmoud Darwish (Zinn Education Project)

- Support for Immigrant and Refugee Students: Fostering a Safe and Inclusive Learning Environment in California’s PreK-12 Schools (Californians Together)

- Teaching Beyond September 11th (University of Pennsylvania Graduate School of Education)

- Women, Life, Freedom: Discussing #Mahsaamini and Feminist Movements in the Classroom (Johns Hopkins SAIS Rethinking Iran)

Webinars & Videos

- The Arab American Experience (Comcast Newsmakers)

- Arab American Heritage Month Webinar: Immigrant to EL Instructor (TESOL International Association)

- Arab | How You See Me (Participant)

- Don't Erase Me: The Modern Arab American (TEDxOhioStateUniversity)

- We’re Not White | Amer Zahr (TEDxDetroit)

- Why We Need Arab American Heritage Month (NowThis)

Podcasts

- Arab American Café

- A podcast by Arab Americans about America and Arabs everywhere, bringing you a unique perspective, both in English & Arabic but mostly in "Arablish.”

- Citizens of Two Worlds

- Citizens of Two Worlds a limited podcast series, produced by Randa Samih Abdu, that looks to identity issues among first generation Arab-Americans in Tucson.

- The Queer Arabs

- The Queer Arabs podcast is a growing collection of dialogues surrounding the intersection of Middle Eastern/Southwest Asian + North African and LGBTQ identities.

- See Something Say Something

- See Something Say Something is an award-winning podcast that covers the social, cultural, and political experiences of American Muslims. Hosted by writer Ahmed Ali Akbar, the show discusses everything American Muslims are talking about, from jinns to representation in media.

- This Muslim Girl Podcast

- This Muslim Girl is an Arab American woman born in Yemen raised in the Central Valley of California sharing stories to empower women.

- True Talk by NPR

- True Talk focuses on the Middle East and the Muslim world. The show also discusses issues that Muslims face world wide, as well as for American Muslims who are seeking to live as peace-loving Americans in a nation that often has only seen stereotypical portrayals of Islam.

American pop cultures that is inclusive of Arab American communities

Movies and TV shows can provide a window into the lives and cultures of the characters depicted in ways that can both dismantle and reinforce cultural stereotypes. When consuming movies and TVs shows that depict characters and cultures different from your own, be careful not to allow the dramatization to nurture harmful stereotypes. No cultural dramatization can fully represent the spectrum of human qualities, characteristics and cultures of any particular group of people.Movies & Documentaries

- American Arab (2013) NR

- Usama Alshaibi, an Iraqi-American filmmaker, confronts the issues on identity and perception toward Arab-Americans in today's society. Alshaibi conveys to the audience that Arab-Americans should not be put into one, big, identical group; rather the culture consists of a diverse group of identities and voices.

- Amreeka (2009) PG-13

- A drama centered on the trials and tribulations of a proud Palestinian Christian immigrant single mother and her teenage son in small town Indiana.

- The Citizen (2012) PG-13

- An Arab immigrant wins the American green card lottery, arriving in New York City on September 10, 2001.

- Celebrate Arab American Heritage Month (PBS)

- This is a list of films and documentaries created by Arab American filmmakers about Arab American communities.

- Detroit Unleaded (2012) NR

- An ambitious Lebanese-American youth is forced to take over his family's gas station after his father's death.

- Marjoun and the Flying Headscarf (2019)

- A teenager in Arkansas searches for identity in the headscarf and a motorcycle in the aftermath of her father's imprisonment. Set in 2006, the film explores the results of Arab and Muslim Americans being increasingly detained for “guilt by association.”

- Persepolis (2007) PG-13

- A precocious and outspoken Iranian girl grows up during the Islamic Revolution.

TV Shows

- American Eid (2021)

- Ameena, a homesick Muslim Pakistani immigrant, wakes up on Eid to find out she has to go to school.

- Arab American Stories (2012)

- Hosted by NPR's Neda Ulaby, ARAB AMERICAN STORIES highlights the diversity of the Arab-American experience and traces the impact of this ethnic group on American institutions and public life. The documentary series profiles entrepreneurs, innovators, educators, artists, doctors, lawyers, executives and others making an impact in their communities, their professions, their families or the world at large, with each character-driven story highlighting universal themes and issues.

- Lady Parts (2021-present)

- A look at the highs and lows of the band members that make up a Muslim female punk band, Lady Parts, as seen through the eyes of Amina Hussein, a geeky PhD student who is recruited to be their unlikely lead guitarist.

- Ramy (2019-present)

- In New Jersey, Ramy, son of Egyptian immigrants, begins a spiritual journey, divided between his Muslim community, God and his friends who see endless possibilities.

Bio-Social-Emotional Needs of Immigrant Students, with a Focus on Central Americans

Bio-Social-Emotional Needs of Immigrant Students, with a Focus on Central Americans

Part of CEE’s Exploring Equity Issues series, this paper discusses social and emotional learning (SEL) and the special challenges faced by immigrant students in this area. For immigrant students, the challenge of SEL is compounded by their simultaneous navigation of social and academic displacement, trauma, and family reunification. The paper concludes with both school-wide and teacher strategies that respond to immigrant student needs.

Bio-Social-Emotional Needs of Immigrant Students, with a Focus on Central Americans

PART I: BACKGROUND

Social and emotional learning (SEL) is the process by which individuals learn to understand and manage their emotions, maintain positive relationships, and make responsible decisions. For immigrant students, this process holds additional challenges, as they learn these skills while also navigating complex emotional reactions to social and academic displacement, trauma, and family reunification. “I am from El Salvador. My uncle, brother and I decided to come to the U.S. because the gangs were threatening us. One of my friends was killed. On the way here we were kidnapped in Mexico and held for three months until a ransom was sent. There was another man with us who had all five of his fingers on one hand cut off by the kidnappers, and then they stabbed him to death right in front of my brother and I. Once we got to the border, we were caught by ICE and my uncle was sent back home. I saw a counselor when I first got here, and now I don’t have nightmares anymore.” HISTORY OF IMMIGRATION AND CURRENT TRENDS Immigration to the United States from Central America has long been driven by economic difficulties and violence. In the last four decades, these countries have experienced civil wars, crippling poverty, increased gang violence and narco-trafficking, and disintegration of civil structures. According to World Atlas statistics, since 2014 El Salvador and Honduras have been named as countries with the highest murder rates that are not at war. Children are either targeted for recruitment into an expansive network of gang activity or are living under their threat. Consequently, the flow of children entering the United States has increased as they seek safety. These children do not have refugee status, but rather must independently find and fund legal counsel. Without such assistance, they risk being deported to the countries they fled. From the years 2013-2015, the Migration Policy Institute reported a spike in Central American unaccompanied minors crossing the Mexican border into the United States, totaling 77,000 during this period. High Point High School in Prince George’s County, Maryland, currently has the largest numbers of ESOL students in the state. The total 2017-2018 ESOL enrollment thus far has topped 1,200 students. With increased anxiety over changing immigration policies, ESOL students are withdrawing or transferring to other schools at unseen rates; over 400 ESOL students have withdrawn from High Point this academic year. Students report that they are receiving deportation and voluntary departure notices, are re-locating to more affordable housing, or are choosing to work in order to prepare for a return to their home country, in spite of the safety risks. BIO-SOCIAL-EMOTIONAL NEEDS Newcomer immigrant students place particular demands on school staff, not only for specialized instructional interventions, but for social and mental health supports as well. Improving instruction requires awareness of intercultural communication and appropriate responses to students exposed to trauma, family loss, uncertain legal future, and cultural adjustment. Immigrant children are more likely to face numerous risks to healthy development (Close & Solberg, 2008). Biological needs to consider include access to health care and immunizations, interruption of eating/sleeping patterns, pre-existing health conditions, and the impact of chronic stress and trauma on the body. Limited exposure to sun and physical exercise also take their toll on newcomer immigrants from countries where most of their daily life took place outdoors. Social needs for belonging within their academic community cannot be overstated. A study of Latino students in the United States confirmed that students who felt more connected with their teachers and their school were also more motivated to attend school, which was in turn associated with better achievement (Close and Solberg, 2008). Newcomer students need opportunities to build relationships with their new peers, experience success in their new language and school, and begin the long task of attachment at home with biological parents or caretakers who may be virtual strangers. Newcomer students also need assistance with acculturation and orientation regarding school procedures, U.S. education norms, legal requirements such as attendance and immunization, and community resource information on low-cost health care and legal services. The students need an opportunity to understand that their culture shock, adjustment, and challenging relationships with unfamiliar family members in the context of time – that their current emotional state, be it stress, depression or anger, is temporary. In 2016, High Point conducted an anonymous survey of 294 newcomer students from Central America to help understand the scope of their social-emotional needs. Responses revealed that 52% had experienced gang/community violence in their home countries or on their journey to the United States, 35% had interrupted education, 45% had a loved one die in the previous year, 37% reported experiencing insomnia or nightmares regularly, and 79% reported a need for legal counseling. As trauma research has documented, children who have experienced trauma, fear, separation from family, and isolation are subject to a variety of psychological stressors and mental health challenges. Studies have shown some develop anxiety, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), or other conditions. Once in the United States, these students continue to worry about family members and friends who remain in their country; family members become ill, friends are murdered, relatives disappear. Trauma can cause interrupted sleep, poor concentration, anger/aggression, physical pain and/or social withdrawal. Trauma also can interfere with attention, memory, and cognition – all skills that are fundamental in learning.PART II: WHAT CAN WE DO?

SCHOOL-WIDE INTERVENTIONS Provide staff training on behaviors to watch for. School-wide interventions begin with training staff so educators are familiar with the geo-political causes of immigration, and the impacts of trauma. Staff training is necessary in order to understand and interpret behaviors a student may exhibit during their adjustment period – be it silence, disorganization, or disengagement. Provide immigrant students with specialized orientation. School staff can also provide a sense of safety to students and facilitate mastery of their new surroundings through teaching expectations and routines with visual reminders, supporting a culture of respect, and correcting with warm firmness. Bilingual orientation guides help with the task of mastery. These guides may include: a map of the school; information on community resources; important staff to know; websites and apps that can support English language learning; school procedures regarding code of conduct, absences, library use, and inclement weather policies; tips for managing culture shock; and strategies for building trust with new family members. Bilingual social work and family support staff are vital. School staff must also help newcomer students be aware of gang activity. Unaccompanied minors in particular are at an increased risk for recruitment either at school or in their communities. Students need to know the methods for recruitment (intimidation, skipping parties, drug trafficking), refusal techniques, and school staff who can support them. TEACHER INTERVENTIONS As teachers, we can draw on the research and interventions for trauma-informed and trauma-sensitive learning environments to respond to immigrant student needs. Marlene Wong of the Support for Students Exposed to Trauma program has designed school-based curriculum to support school-wide understanding and interventions to mitigate the impact of past trauma. All the best instructional techniques we have will depend on the student’s availability to engage with and learn from us. This need to belong has long been recognized as one of the most important psychological needs in humans (Maslow, 1943). Hence, our most essential tool in engaging with all youth, especially youth with traumatic histories, is ourselves – our warm, caring, dependable, steady, relational, limit-setting selves. As educators and support staff, we provide this necessary positive mirroring and a belief that students’ resilience is stronger than their challenges. Use mindfulness techniques in the classroom. Resiliency and post-trauma growth research emphasizes the need for students to learn emotional regulation, how to relate positively to others, and how to reason through challenges. Mindfulness techniques and grounding exercises can help students by teaching an awareness of their body and their mind in the present moment. Using five minutes of class on a routine bases for check-ins related to self-awareness (emotional state, physical and cognitive energy), deep breathing techniques, guided meditation, and simple movements to stimulate or calm the brain are all skills that students can learn in order to regulate their mind and body. These exercises can change the energy of the student and the energy in the classroom. Engage in classroom community building. The circle process is another method for strengthening classroom community and enhancing self-efficacy. Using one or two prompts and inviting students to respond provides an opportunity to build connections and normalize their experiences of adjustment. In addition, invite older student leaders who have lived through similar experiences, to share their challenges and successes with newcomer students. Given the changes in immigration policies specifically towards Central American students and families, we are likely to see an increase in anxiety-related and depressive behaviors. This could be manifested by poor attendance, self-harm and suicidal ideation, increased drug use, and dropping out of school. As caring educators, we need to know the daily realities of our students and how we can best address their needs, to support what they most desire – a safe and better life for themselves and their families.RESOURCES

- Helping Traumatized Children Learn

- National Child Traumatic Stress Network

- Niroga

- BRYCS: Refugee Children in U.S. Schools: A Toolkit for Teachers and School Personnel

REFERENCES

Blaustein, M., & Kinniburgh, K. M. (2010). Treating traumatic stress in children and adolescents: How to foster resilience through attachment, self-regulation, and competency. New York: Guilford Press. Boyes-Watson, C., & Pranis, K. (2015). Circle forward: Building a restorative school community. St. Paul, MN: Living Justice Press. Close, W., & Solberg, S. (2008). Predicting achievement, distress, and retention among lower-income Latino youth. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 72(1), 31-42. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2007.08.007 Eccles, J. S., & Roeser, R. W. (2011). Schools as Developmental Contexts During Adolescence. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 21(1), 225-241. doi:10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00725.x Maslow A. H. (1943). A theory of human motivation. Psychol. Rev., 50 370–396. \10.1037/h0054346 National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance (NCEE) home: Part of the U.S. Department of Education (ED). (n.d.). Retrieved March 21, 2018, from https://ies.ed.gov/ncee/edlabs/ Pariona, A. (2016, September 28). Murder Rate By Country. Retrieved March 21, 2018, from https://www.worldatlas.com/articles/murder-rates-by-country.html What is SEL? (n.d.). Retrieved March 21, 2018, from https://casel.org/what-is-sel/

Building Leaders: An Educator’s Guide to Family Leadership

Building Leaders: An Educator’s Guide to Family Leadership

Develop family leadership programs that increase engagement and support for families in positive ways using inclusive and diversity-focused strategies. Learn how to update family leadership programs to consider students' and families' diverse knowledge and tools for success. A successful leadership program must identify and work with a family's unique needs, experience, and knowledge to establish a strong relationship and trust. Educators can use the MAEC Family Engagement Model to transform family leadership programs for inclusivity using intentionally collaborative approaches that focus on relationship building, knowledge and skills, confidence and efficacy, and advocacy. This resource offers detailed overviews of 12 family leadership models addressing the needs of diverse populations, testimonial insights from educators and family leaders, and resources for each area of the model.

Link: https://maec.org/building-leaders/

Building Relationships for Student Success

Building Relationships for Student Success

Part of CEE’s Exploring Equity Issues series, this paper discusses the importance of building relationships with students in schools, classrooms, and out-of-time school programs. It also provides principles and practices that educators have used to build positive relationships and school cultures.

Building Relationships for Student Success

PART I: RELATIONSHIPS WITH STUDENTS MATTER As the National Scientific Council on the Developing Child concluded in a 2004 report, “relationships engage children in the human community in ways that help them define who they are, what they become, and how and why they are important to other people.” Or as researchers Junlei Li and Megan Julian have argued, interventions that don’t focus on relationships are as effective as toothpaste without fluoride (Li & Julian, in press). How do you build positive relationships with students in schools, classrooms, and out-of-time school programs? How do these relationships contribute to the overall culture of the learning environment in schools? Why is this particularly important for students who have to overcome challenging childhood experiences? Data show the more positive relationships that students have, the more likely they are to be successful in school and in their lives (Roehlkepartian & Pekel et. al, Science Research, 2017). Again, this is particularly true for our more vulnerable students who may face challenging situations outside of school and need adults at school who can engage and motivate them. Schools are small societies. These small societies are usually under considerable stress because they must perform in the context of many internal and external demands. All too often a sense of siege results and a garrison mentality can arise. One of the pioneers in the sociology of education, Willard Waller, characterized school culture as “a despotism in a state of perilous equilibrium.” But Waller’s vision is too bleak. Schools can be joyful and exciting places to learn if attention is paid to ensuring and promoting healthy relationships among students, teachers, administrators, staff, families, and the community. The sum total of these relationships is a school’s culture and building them must be a priority. Harvard educator Roland Barth (2002, p.6) once observed, “A school’s culture has far more influence on life and learning in the school house than the president of the country, state department of education, the superintendent, the school board, and even the principal, teachers and parents can ever have.” According to the Great Schools Partnership, the term “school culture”generally refers to the beliefs,perceptions, relationships, attitudes, and written and unwritten rules that shape and influence every aspect of how a school functions. The term also encompasses more concrete issues such as the physical and emotional safety of students, the orderliness of classrooms and public spaces, or the degree to which a school embraces and celebrates racial, ethnic, linguistic, or cultural diversity. The importance of a positive school culture based on health and productive relationships for student success is supported by research. James Coleman and his associates, in particular, brought to public attention the power of positive relationships and school cultures in shaping student achievement. Since their 1981 publication, High School Achievement: Public, Catholic, and Private Schools Compared, the study of school cultures has grown to include the work of other scholars such as Anthony Bryk and Barbara Schneider (2004), whose study of trust makes it clear that healthy relationships build trust which in turn leads to inclusive and productive learning environments. A school’s culture reveals its underlying ethos and its unspoken assumptions about the value of relationships. These characteristics matter to young people seeking to find themselves and envision a positive future. Capturing this organizational magic in a bottle is not an easy task, but to ignore the cultural DNA of schools is to overlook their potential power to transform lives. Positive relationships which help to build positive school cultures, however, are not ends in themselves. The goal is to create great schools and school systems that unleash human talent by becoming genuine learning communities. As Adams, Ford, and Forsyth (2015) write: Teachers learn and grow from personal and shared reflections of teaching practice. Principals leverage trust and commitment to bring transformative visions to life. Students are motivated and engaged when they relate to instructional materials and find meaning in academic tasks. Learning opportunities expand when schools, families and communities establish relational cohesion. Today the issue of building relationships for student success is critically important. Roughly half the country’s public school students are eligible for free or reduced priced meals. Less than half the students enrolling in public schools today are white. We are a multicultural, multiracial, and multilingual society. We must learn to celebrate differences and work together for the common good. These positive relationships begin at the school house door. What can we do on a practical basis to ensure that we build positive relationships and school cultures so all students succeed? PART II: WHAT CAN WE DO? The elements that contribute to positive relationships and school culture include: building trust, conveying care, stimulating growth, sharing decision making, increasing possibilities (Search Institute, 2017), a safe and supportive environment, effective school leadership, culturally responsive pedagogy and practice, high quality teachers, rigorous instruction, numerous extracurricular activities, staff collaboration, and college and career readiness. The bedrock quality of a positive school culture is the inclusion of family and community. Community is a big concept; inclusion means everyone. Below are some principles and practices that educators have used to build positive relationships and school cultures: ADHERE TO AND INTERNALIZE BASIC PRINCIPLES The first step is a commitment to basic principles including: Relationships with students matter. First and foremost, time, effort, and caring can result in increased student engagement and higher academic achievement. Professional learning opportunities to develop relational skills are vital to creating a positive learning environment. A school’s vision and mission should be based on a co-constructed approach between schools, diverse families, and communities where all cultures are elevated and respected. Differences in culture and language should be seen as assets and funds of knowledge. Policies and practices should be aligned with specific needs of students. It is imperative that program offerings are aligned to teach and assess diverse students, including English Learners, African American, Latino children, and other populations whose academic achievement needs to be addressed to reduce and eliminate the achievement gap. School leaders must set the tone and demonstrate consistent commitment to inclusion and mutual respect. Leadership is essential to the success of building a positive school culture. Successful school leadership requires both modeling and implementing practices that include the whole community in decision making. Teachers need embedded professional learning opportunities to empower them to act as agents of change. On-going culturally competent professional development enables teachers to learn skills and receive support as needed. POSITIVE SCHOOL CULTURES INCLUDE FAMILY AND COMMUNITY We know there are certain policies and practices which increase learning for all students and promote inclusive and supportive school cultures. Here are some suggestions: Communicate regularly with families, community, and the public. All positive relationships are based on open and honest communication. No one in a school should feel silenced. Communicate positive information about students to their families. Build on identified family resources and their funds of knowledge. This will help create authentic engagement to increase and sustain academic achievement (e.g. home visiting programs). Revise or refine the school’s discipline code with student and family input Emphasize understanding and reconciliation rather than punishment. Reflection is critically important for creating positive relationships. By embracing diversity and, by recognizing the worth of all people, schools can change from the inside-out in a genuine organic way and become nurturing environments where positive relationships develop and thrive. And students develop and thrive. Written by Peter W. Cookson, Jr. - Principal Researcher, American Institutes for Research. Edited by Susan Shaffer - President, MAEC REFERENCES Adams, C., Ford T. & Forsyth P. (2015). Next generation school accountability: A report commissioned by the Oklahoma State Department of Education. Tulsa, OK: The Oklahoma Center for Education Policy & the Center for Educational Research and Evaluation. Bryk, A. S. & Schneider, B. (2004). Trust in schools: A core resource for improvement. New York: The Russell Sage Foundation. Barth, R. S. (2002). The culture builder. Educational Leadership, 59 (8), 6–11. Coleman, J. S., Hoffer, T., & Kilgore, S. (1981). High school achievement: Public, Catholic and private schools compared. Chicago: National Opinion Research Center. Li, J., & Julian, M. M. (2012). Developmental relationships as the active ingredient: A unifying working hypothesis of “what works” across intervention settings. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 82(2), 157–166. doi10.1111/J.1939-0025.2012.01151.X National Scientific Council on the Developing Child. (2004). Young children develop in an environment of relationships. Working Paper No. 1. Cambridge, MA: National Scientific Council on the Developing Child, Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University. Retrieved from https://developingchild.harvard.edu/wp-content/uploads/2004/04/Young-Children-Develop-in-an-Environment-of-Relationships.pdf. Roehlkepartain, E. C., Pekel, K., Syvertsen, A. K., Sethi, J., Sullivan, T. K., & Scales, P. C. (2017). Relationships First: Creating Connections that Help Young People Thrive. Minneapolis, MN: Search Institute. Search Institute. (2017, May). The developmental relationships framework. Retrieved from https://www.search-institute.org/developmental-relationships/developmental-relationships-framework/ Download: Exploring Equity - Building Relationships with StudentsCOVID-19, Racism and Xenophobia: A Discussion on How and Why the Pandemic is Affecting Asian Americans

- Hilario Benzon

- Merwyn Scott

- Gabriel Tanglao

- Nyla Bell

- Gabriel Tanglao

- Jason Oliver Chang

- Michelle Nutter

- Fred Pinguel

- Noreen Rodriguez

- Yan Yii

Creating New Futures for Newcomers

Creating New Futures for Newcomers

Lessons from Five Schools that Serve K-12 Immigrants, Refugees, and Asylees Given the influx of immigrants and refugees over the past several years, newcomer students are found in the classrooms of small towns, suburbs, and big cities across the country and they bring with them a world of culturally diverse experiences and knowledge. Newcomers face myriad challenges to adapt and succeed in their new home and schools. They must learn how to navigate a new culture socially, master a new language, and adjust to a new, and typically different, educational system. Many of these students enter our schools with little or no formal education or fluency in English. Some have fled terrible conditions in their homelands. Others are here without their families. Despite these challenges, all share dreams of being successful students and productive members in our communities, while remaining linked to their cultures and native languages as they become first generation Americans. To help make these dreams come true, we searched for “bright spots,” schools that offer promising and effective strategies for newcomers in K-12 classrooms. In this report, we focus on five very different schools that serve newcomers, each offering promising strategies, proven approaches, and fresh ideas that can benefit all educators, but especially those who work with immigrant and refugee students. We discuss curriculum and instruction, professional learning, school orientation, social-emotional and health support, and ways to partner with newcomer families and communities. We learn how newcomer schools assist students to adjust and thrive. This report was developed through a partnership between MAEC and WestEd. The main author is BethAnn Berliner, Senior Researcher/Project Director at WestEd. Click here for more information and to download the publication.

Criteria for an Equitable School – Equity Audit

Criteria for an Equitable School – Equity Audit

This tool helps school leaders assess whether or not the school provides the processes and information which create a positive learning environment so students and staff can perform at their highest level. To download this, and the other Equity Audit tools, please go to MAEC's Equity Audit page.

Download: Criteria for an Equitable School-2020-accessible

Culturally Responsive Leaders

Culturally Responsive Leaders

Part of CEE’s Exploring Equity Issues series, this paper examines why it is important for educators to be culturally responsive leaders in order to address the needs of their culturally and linguistically diverse learners. Using one of CEE's case studies, it highlights several preconditions necessary for achieving this and outlines the Essential Elements of Cultural Competence.

Culturally Responsive Leaders

PART I: TIMES HAVE CHANGED, AND THEY HAVEN’T The National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) reports that in 2014,students of color represented slightly more than half (50.5%) of all public school students, an increase from 38.8% in 2000 (McFarland et al., 2018). Meanwhile, teacher demographics have remained stagnant. NCES data list 81.9% of public school teachers in 2012 as White (the latest year available), a small decrease from 84.3% in 2000 (Musu-Gillette et al., 2016, US ED, 2016). They are not just White; they are predominantly White, female, and middle class. Why is this important? Research shows that students’ race, ethnicity, and cultural background significantly influence their achievement (Aceves & Orosco, 2014). Yet many teachers are inadequately prepared to address the needs of their culturally and linguistically diverse learners (Skiba, et al., 2011; Darling-Hammond, 2010; Miller, 2009). Culturally responsive teachers can close the achievement gap by fostering academic optimism, raising expectations of excellence, connecting with each student’s prior knowledge, and delivering content knowledge in ways students can understand (Ball & Forzani, 2011; Farr, 2010; Brown et al., 2009; Miller, 2009). Culturally responsive leaders nurture and maintain high-quality teaching, and foster an inclusive community that builds on teacher, student, and family assets. The recognition that schools need culturally responsive teachers and leaders is not new. In 2005, the Institute for Educational Leadership (IEL) published a report on preparing and supporting diverse, culturally responsive leaders (then referred to as culturally competent leaders). It grew out of a series of meetings among practitioners in the field. It was intended to provide field-based insights from people working in/with leadership development programs for school leaders across the country. The report outlined five themes: 1. Educational leaders who are not culturally competent cannot be fully effective. 2. Culturally competent leaders work to understand their own biases as well as patterns of discrimination. They have the skills to mitigate the attendant negative effects on student achievement and the personal courage and commitment to persist. 3. Much of what culturally competent leaders must know and be able to do is learned in relationships with families and communities. 4. Culturally competent leadership develops over time and needs to be supported from preparation through practice. Creating collaborative frameworks and structures can be useful. 5. State and local policies need to build a sense of urgency about preparing culturally competent leaders (IEL, 2005). A Case Study CEE engaged in a technical assistance project with a school district that was designed to assist educators in becoming culturally responsive leaders. This district of 3,600 students had four elementary schools, one middle school, and one high school. Its student population was 77% White, 3% African American, 13% Asian, 4% two or more races, and 4% Latino/a. Less than 1% were English learners and 4% were economically disadvantaged. One of the superintendent’s priorities for the school year was for district staff to develop an understanding of the importance of culturally responsive pedagogy and practice. He requested assistance to facilitate conversations on race, class, and gender. The district had received three complaints from families who reported receiving unfair treatment. He recognized the challenges of addressing potentially deeply-rooted biases. CEE began work at the elementary school with the greatest diversity of students. CEE offered a professional development workshop to about 50 school staff along with the superintendent. The workshop was designed to allow persons of different backgrounds to gain an understanding of culturally responsive teaching in a non-threatening way. It focused on developing an understanding of how cultural background and prior experiences shape mindsets and worldviews. The goal was for teachers to be able to use this information to shape how they engage with and support students from diverse backgrounds. The session provided an opportunity for teachers and the superintendent to discuss reports from some families regarding their discomfort in the district and how the district could implement strategies to address these concerns. Initial teacher response to the session was generally positive, but teachers questioned why the district was offering this session. They also appreciated having an opportunity for discussion and the reminder that people are defined by so many characteristics. But they would have liked to have been given suggestions on how to treat students more equitably and given more time to brainstorm together to come up with a plan and tools for engaging parents in this work. CEE conducted a discussion with a smaller group of school and district staff to see how to move the project more quickly. They agreed to focus on facilitating sessions among teachers to help them feel less defensive and become more open to addressing issues of culture and equity in the district. To be successful, staff need the rationale behind the professional development so that they are better prepared to engage in difficult conversations. PART II: WHAT CAN WE DO? There are many preconditions to becoming a culturally responsive leader. Our case study highlighted the following lessons learned: FOSTER RELATIONSHIPS Foster relationships between district leadership and staff to discuss issues such as school climate, cultural responsive pedagogy and practice, authentic family and community engagement, and equitable opportunities for students. Culturally responsive leaders have the capacity to break down systems of practice that perpetuate inequities. They need to engage people from different cultures and to act as cultural brokers. This means they must communicate effectively a culturally responsive vision and goals, not always an easy task. They must simultaneously be a catalyst for change while handling dissonance. Above all, they need to create a safe environment for courageous conversations about cultural responsiveness, and where people are held accountable. BUILD TRUST FIRST Build trust and establish relationships prior to providing professional development. This will enable staff to acknowledge, accept, and reflect on their own biases and potential consequences for their school or district. This valuable reflection time will more likely lead to buy-in from staff and enable sustainability. The staff also needs professional supports to engage in this challenging work. BE TRANSPARENT Be transparent about the reasons for professional development and create a thriving, culturally responsive professional learning community. Provide the rationale for the professional development so participants are better prepared to engage in difficult conversations. Culturally responsive leaders are vulnerable with staff as they engage in these discussions. As the case studied showed, teachers questioned why they were attending this particular topic for professional development. A thriving, culturally responsive professional learning community supports adult learning that is reflective of student racial and cultural backgrounds and includes educator of color voices. CULTIVATE STRONG LEADERS Cultivate strong leadership within the school building and district to build and sustain the necessary cultural and instructional changes. Culturally responsive leaders need an understanding of critical theories about how people learn. They also need to know the impact of race, power, legitimacy, cultural capital, poverty, disability, ethnicity, gender, age, language, and other factors on learning. Equally important, they need to understand patterns of discrimination, inequalities, and injustice associated with individual groups. Finally, they need to be able to articulate their own philosophy of education and to examine whether they use it to maintain the status quo or to empower others’ active participation in their own transformation. KNOW YOUR DISTRICT AND YOUR BUILDING Whether using an external consultant or a qualified district staff member, devote sufficient time to learn about your district characteristics, needs, and interests. A culturally responsive leader knows who is in their district and who is in the building and community. Addressing cultural responsiveness requires a tailored approach. Culturally responsive leaders should understand the cultural history of their schools, families, and communities. They should aim to possess a global perspective. Culturally responsive leaders also know and question their own values, commitments, beliefs, prejudices, and uses of power and influence. They must be able to understand a variety of contexts and situations and to accept challenges that arise. Conclusion Culturally responsive leadership improves learning (Darling-Hammond, 2010). The work of educational leaders is to ensure that teachers have the knowledge and skills necessary to ensure that every student receives the highest quality instruction every day. When educational leaders lack cultural understanding, they may react defensively in the face of diversity to maintain the status quo (IEL, 2005). When educational leaders understand the cultural context, they can set a tone for collaboration and facilitate academic excellence. Written by Phoebe Schlanger, MAEC The Essential Elements of Cultural Competence #1 ASSESSING CULTURAL KNOWLEDGE What would a culturally responsive leader do? Assemble his/her collaborative leadership team to reassess the extent to which cultural knowledge of students is clearly present in the school’s vision and mission. #2 VALUING DIVERSITY What would a culturally responsive leader do? Conduct a school climate survey and determine whether school policies and procedures value cultural diversity. #3 MANAGING THE DYNAMICS OF DIFFERENCE What would a culturally responsive leader do? Examine and monitor the extent to which Culturally Responsive Classroom Management and Culturally Responsive Positive Behavior Supports and Management Systems are in place and contribute to reducing the frequency of discipline referrals, suspensions, and expulsions. #4 ADAPTING TO DIVERSITY What would a culturally responsive leader do? Monitor the extent to which s/he strategically and systematically engages teacher leaders in collaborative inquiry as a means for transforming the process of decision making. #5 INSTITUTIONALIZING CULTURAL KNOWLEDGE What would a culturally responsive leader do? Examine the extent to which the protocols for teacher placement, teacher performance observation, and teacher evaluation take into account the experience of schooling of students who are disproportionately underserved. REFERENCES Aceves, T. C., & Orosco, M. (2014). Culturally responsive teaching (Document No. IC-2). Retrieved May 25, 2018 from University of Florida, Collaboration for Effective Educator, Development,Accountability, and Reform Center website: http://ceedar.education.ufl.edu/tools/innovationconfigurations/ Ball, D. L., & Forzani, F. (2011). Teaching skillful teaching. Educational Leadership, 68(4), 40-45. Basterra, M. d., Trumbull, E., & Solano-Flores, G. (2011). Cultural validity in assessment: Addressing linguistic and cultural diversity. New York: Routledge. Brown, R., Copeland, W., Costello, E., Erkanli, A., & Worthman, C. (2009). Family and community influences on educational outcomes of Appalachian youth. Journal of Community Psychology, 37(7): 795–808. doi: 10.1002/jcop.20331 CampbellJones, B., CampbellJones, F., & Love, N. (2009). Bringing cultural proficiency to collaborative inquiry. In N. Love (Ed.), Using data to improve learning for all: A collaborative inquiry approach (80-95). Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press. Cross, Terry L., Bazron, Barbara J., Dennis, Karl W., and Isaacs, Mareasa R. (March 1989). Towards a culturally competent system of care: A monograph on effective services for minority children who are severally emotional disturbed. Georgetown University Child Development Center. Retrieved May 25, 2018 from https://spu.edu/~/media/academics/school-ofeducation/Cultural%20Diversity/Towards%20a%20Culturally%20Competent%20System%20of%20Care%20Abridged.ashx Darling-Hammond, L. (2010). The flat world and education: How America's commitment to equity will determine our future. New York: Teachers College, Columbia University. Farr, S. (2010). Teaching as leadership: The highly effective teacher's guide to closing the achievement gap. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Hanover Research (August 2014). Strategies for building cultural competency. Retrieved May 25, 2018 from http://www.gssaweb.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/Strategies-for-Building-CulturalCompetency-1.pdf Institute for Educational Leadership. (2005). Preparing and supporting diverse, culturally competent leaders: practice and policy considerations. Washington, DC. ISBN 1-933493-01-1 McFarland, J., Hussar, B., Wang, X., Zhang, J., Wang, K., Rathbun, A., Barmer, A., Forrest Cataldi, E., and Bullock Mann, F. (2018). The condition of education 2018 (NCES 2018-144). U.S. Department of Education. Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics. Retrieved May 25, 2018 from https://nces.ed.gov/pubsearch/pubsinfo. asp?pubid=2018144 Miller, M. (2009). Teaching for a new world: Preparing high school educators to deliver college and career-ready instruction [Policy Brief]. Washington, DC: Alliance for Excellent Education. Musu-Gillette, L., Robinson, J., McFarland, J., KewalRamani, A., Zhang, A., and Wilkinson-Flicker, S. (2016). Status and trends in the education of racial and ethnic groups 2016 (NCES 2016-007). U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics. Washington, DC. Retrieved May 30, 2018 from http://nces.ed.gov/pubsearch. Reform Support Network. (2015). Promoting more equitable access to effective teachers: Strategic options for states to improve placement and movement. Retrieved May 25, 2018 from: https://www2.ed.gov/about/inits/ed/implementation-supportunit/techassist/equitableaccesstoeffectiveteachersstrategicoptions.pdf Skiba, R.J., Honer, R.H., Chung, C-G, Rausch, M.K., May, S.L., & Tobin, T. (2011). Race is not neutral: A national investigation of African American and Latino disproportionality in school discipline. School Psychology Review, 40(1), 85-107. Bloomington, IN: National Association of School Psychologists. The Aspen Education & Society Program and the Council of Chief State School Officers. (2017). Leading for equity: Opportunities for state education chiefs. Washington, D.C. U.S. Department of Education, Office of Planning, Evaluation and Policy Development, Policy and Program Studies Service (2016). The state of racial diversity in the educator workforce.Washington, DC. Retrieved May 25, 2018 from http://www2.ed.gov/rschstat/eval/highered/racialdiversity/state-racial-diversityworkforce.pdf. Download: Exploring Equity - Culturally Responsive Leaders

Engaging Immigrant and English Learner Families in their Children’s Learning

Engaging Immigrant and English Learner Families in their Children’s Learning

While the benefits of family engagement are well known, reaching immigrant parents and caretakers present many challenges – from both sides: educators and immigrants.

Engaging Immigrant and English Learner Families in their Children’s Learning

PART I: THE LONG ROAD TRAVELED

Last month, Exploring Equity Issues focused on the multiple obstacles that immigrant students face adjusting to their new lives in the United States. This month we address their families, specifically, engaging them in their children’s learning. While the benefits of family engagement are well known, reaching immigrant parents and caretakers present many challenges – from both sides: educators and immigrants. Why is it important to engage immigrant and English Learner (EL) families? According to the 2016 Current Population Survey, immigrants and their U.S.-born children now number approximately 84.3 million people, or 27 percent of the overall U.S. population. In 2015, English Learners (ELs) ages 5 and older represented nine percent of the U.S. student population (Migration Policy Institute, 2017). A QUICK RECAP ON FAMILY ENGAGEMENT More than 50 years of research indicate that family engagement plays a critical role in supporting children’s learning, encouraging grit, determination, and will to succeed. Moreover, findings show that when families are involved, children improve in a range of areas: better grades, higher scores on achievement tests, lower drop-out rates, regular school attendance, better social skills, improved behavior, leading to better chances students will graduate from high school and continue their education (Henderson & Mapp, 2202; Smith, Stern, & Shatrova, 2008; Hayes, 2012; Shute et al., 2011; Fan & Chen, 2001). YES, BUT WHO GETS INVOLVED? Results of the study Parent and Family Involvement in Education from the National Household Education Surveys Program of 2012, show that Latino and Asian parents are less likely to attend school or class events or volunteer or serve on school committees (National Center for Education Statistics, 2016). While 82 percent of White parents attended school-related events, only 64 percent of Latino parents and Asian parents participated. The same differences can be found in volunteering on school committees. Fifty percent of White parents participated in contrast with 32 percent of Latino parents and 37 percent of Asian parents. The same study also shows differences in parent and caregiver participation when English spoken at home is taken into consideration. Families who speak English at home tend to participate more in schools compared with those who do not. Data indicate that in households where both parents speak English at home, 78 percent participate in class events compared to 62 percent if only one parent speaks English and 50 percent if no parent speaks English. Immigrant families face many barriers as they try to become informed or involved in their child’s school. These barriers, which include limited English proficiency, unfamiliarity with the school system, and differences in cultural norms, can limit communication and participation in schools. Given the increasing number of immigrant families and their relative low levels of engagement with schools, educators should consider the following approaches to promote engagement. It begins with acknowledging and changing some preconceptions. CHANGING MINDSETS Switch to an asset-based approach to immigrant families and their children. Deficit-thinking treats students’ and families’ cultural, language, and socioeconomic characteristics as causes of students’ low academic achievement. Teachers with this perspective perceive immigrant students and their parents as a heavy load that needs to be lifted and assimilated into American society in order to succeed. Research studies have shown, however, that an asset-based model recognizes that the funds of knowledge immigrant families bring to school – including their language – provide a solid foundation for positive and effective interaction between school and families and nurture students’ self-esteem and academic achievement (Gonzalez, Moll, & Amanti, 2005; Bruton & Robles-Piña, 2009). Acknowledge that immigrant and EL families are interested in their children’s educational success. Many schools interpret the low level of engagement as a sign of immigrant and EL families’ lack of interest in promoting educational success. Research indicates that the majority of families, regardless of race, ethnicity, or socioeconomic status, are interested in their children’s educational achievement (Chavkin & Williams, 1993; Henderson & Mapp, 2002). The myth that immigrants do not value education is based on a deficit model that claims they do not have the knowledge or cultural capital to provide their children with high aspirations and a positive attitude (Moreno & Valencia, 2002; Olivos & Mendoza, 2010). This myth has been debunked by research studies and legal actions that document that immigrant families have high expectations for their children’s educational attainments (Gonzalez, Moll & Amanti, 2005; Orozco, 2008). Immigrant families have actively participated to improve the education of their children, including historical litigation cases, advocacy organizations, individual activities, and political demonstrations/legislation where parents and caretakers struggled and advocated for them (Moreno & Valencia, 2002). Recognize that immigrant and EL families have different cultural expectations. Many immigrants come from countries where parents and caretakers are not expected to participate actively in school-related activities. In addition, immigrants face different cultural expectations from teachers and schools (Kao et al., 2013). In other countries, students are expected to learn largely from their teachers. In the United States, however, families are expected to actively engage with the schools in a joint effort to educate their children. In order to address this issue, schools need to acknowledge this fact and develop strategies to inform families about the impact of family engagement and their role in advocating for their children. Con Respeto (Respectfully) - Develop Two-Way Partnerships. Several research studies show that the ways in which schools engage families influences why and how parents participate in their children’s education. A welcoming, honoring, culturally-responsive and positive school environment creates conditions for parents of culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds to participate (Mapp, 2003). The findings of the ethnographic studies of Guadalupe Valdez (1996) marked the beginning of an approach that attempted to change how schools worked with immigrant families. Initiatives to engage immigrants needs to use an approach where parents are seen as equal partners in two-way partnerships rather than passive participants that are invited to follow school-initiated activities.PART II: WHAT CAN WE DO – SPECIFICALLY?

In addition to changing the way immigrant and EL families are perceived and developing two-way partnerships, schools engage and sustain the participation of families of linguistically and culturally diverse backgrounds using the strategies described below: LEARN ABOUT YOUR EL POPULATION The first step in any relationship is to learn about each other. What languages do your immigrant and EL families speak? What countries do they come from? How many of your ELs are migrants, refugees? How many were born in the U.S.? Address these questions in a personal way – not through impersonal surveys. Help your immigrant families see you are interested in them. Parents and caretakers appreciate face-to-face communications. If they have trouble coming into the school – because they have work commitments, transportation challenges, or other reasons – try making phone calls. CREATE A WELCOMING ENVIRONMENT Provide families with information and/or materials in their home language. This should include even informal notices. Post signs in different languages. Establish a family room or bulletin board that highlights their cultures and languages. Embrace their cultures and funds of knowledge as assets for the school curriculum and overall school culture. HIRE FAMILY LIAISONS THAT SPEAK THE MOST COMMONLY USED LANGUAGE(S) IN YOUR EL COMMUNITY When budgets allow, hire school staff who speak the most commonly used languages. Reach out to bilingual parents to help bridge these gaps. Use family-to-family connections at the school and community level. OFFER TRAINING TO YOUR IMMIGRANT AND EL FAMILIES Help your families understand the U.S. public education system. Provide instructions in conversational terms, defining technical jargon clearly (or avoiding it altogether). Teach them how to advocate for their children. Provide family literacy and/or ESL classes. Remember to schedule activities at times when they can attend. Provide child care and interpreters if needed. SUPPORT FAMILIES TO SUCCESSFULLY ENGAGE IN THEIR CHILDREN'S LEARNING Immigrant and EL families may feel they cannot help with their children’s learning because they do not understand English. Reassure them that they can help their children in school even when they do not understand the language. Immigrant and EL families can begin with the same strategies that apply to all families: provide a place where their child can do homework; check that their child completes homework each night; and ask their child to tell them about what he or she learned in school during the day. Then suggest that they read and tell stories in their native language. Engaging immigrant and EL families is crucial to addressing the demands children face as they live and achieve in the U.S. Providing a welcoming, inclusive, and respectful environment to families in our schools helps ensure they are able to offer the support their children need to succeed. Written by Maria del Rosario (Charo) Basterra and Phoebe Schlanger, MAEC.REFERENCES

Bruton, A. & Robles-Piña, R. (2009). Deficit Thinking and Hispanic Student Achievement: Scientific Information Resources. Problems of Education in the 21st Century, 15, 41-48. Chavkin, N. & Williams, D. (1993). Minority Parents and the Elementary School: Attitudes and Practices. In N. Chavkin (Ed.), Families and Schools in a Pluralistic Society (pp. 72-83), Albany: State University of New York Press. Gonzalez, N., Moll, L., & Amanti, C. (2005). Funds of Knowledge: Theorizing Practices in Household Communities, and Classrooms. Mahwah, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Fan, X., X, & Chen, M. (2001). Parental Involvement and Students’ Academic Achievement: A Meta-Analyisis. Educational Psychology Review, 13 (1), 1-22. Hayes, D. (2012). Parental Involvement and Achievement Outcomes in African American Adolescents. Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 43(3), 567-582. Henderson, A. & Mapp, K. (2002). A New Wave of Evidence: The Impact of School, Family, and Community Connections on Student Achievement. Austin, TX: Southwest Educational Development Laboratory. Kao, G., Vaquera, E., & Goyette, K. (2013). Education & Immigration. Polity Press, Malden, MA. Mapp, K. (2003). Having Their Say: Parents Describe Why and How They Are Engaged in Their Children's Learning. School Community Journal, v13 n1 p35-64. Migration Policy Institute (2017). Frequently Requested Statistics on Immigrants and Immigration in the United States. Moreno, R. & Valencia, R. (2002). Chicano Families and Schools: Myths, Knowledge, and Future Directions for Understanding. In R. Valencia (Ed.), Chicano school failure and success. New York: Falmer Press. National Center for Education Statistics (2016). Parent and Family Involvement in Education, from the National Household Education Surveys Program of 2012. US Department of Education. Olivos, E. & Mendoza, M. (2010). Immigration and Educational Inequality: Examining Latino Immigrant Parent’s En-gagement in US Public Schools. Journal of Immigrant & Refugee Studies, 8(3)m 339-357. Shute, S., Underwood, J., Razzourk, R. (2011). A Review of the Relationship Between Parental Involvement and Secondary School Students’ Academic Achievement. Educational Research International. Smith, J., Stern, K., & Shatrova, Z. (2008). Factors Inhibiting Hispanic Parents’ School Involvement. Rural Education, 29(2), 8-13. Valdez, G. (1996). Con Respeto. Bridging the Distances Between Culturally Diverse Families and Schools. An Ethno-graphic Portrait. Teachers College Press Download: Exploring Equity - Engaging Immigrant Parents in Children's Education

Equitable Access to Higher Education

Equitable Access to Higher Education

Part of CEE’s Exploring Equity Issues series, this paper discusses the inequities that exist with culturally and linguistically diverse students in regards to access to college, and to persistence and completion once enrolled. It also discusses policies and practices that can make a difference in helping our most vulnerable youth transition smoothly to college and earn a degree

Equitable Access to Higher Education