Download: MAEC-Rural-Growing up Rural

In their research- and narrative-filled article, Dr. Beverly Boals Gilbert and Dr. Cathy Grace call for action in providing resources to people living in the rural Mississippi Delta. Dr. Grace draws from personal stories growing up and teaching in rural Arkansas, describing the moment she recognized her own learning gaps, the impact of the district’s decision not to integrate schools, and what it was like teaching students without the necessary tools. The authors also draw from other personal stories, including responses from child care professionals who are struggling during COVID-19 closures.

Back to Count Us In: Advancing Equity in Rural Schools and Communities

Growing Up Rural: Inequity for Young Children and Child Care Providers

September 2020: Exploring Equity Issues, Rural Edition

Beverly Boals Gilbert, Ed.D.

Professor, Early Childhood Education, Arkansas State University and

Cathy Grace, Ed.D.

Co-Director, Graduate Center for the Study of Early Learning, University of Mississippi, North Mississippi Education Consortium

Growing up in rural Arkansas and Mississippi, we did not know what we did not know. We knew about dirt roads, walking the railroad tracks, church socials, Dick and Jane basal readers, and how to shell peas. We didn’t know how isolated we were, what a public transportation system looked like, and what a rigorous curriculum required. One of the things about being a young child who lives in a rural community where everyone has the same life as you, or worse, is that you don’t know you’re being left behind or left out.

Cathy’s Story

This was taken 45 years ago at my Daddy’s store. I am on the left, a parent is in the middle, and the county librarian is on the right. This was my first ”kindergarten.” The children would walk to Daddy’s store and we would read and learn basic skills like ABC’s. They would all receive a complimentary ice cream at the end of the weekly “class.” The librarian would leave a shelf of books for the children to check out and return during the week.

My family was fortunate. Even if I did bathe in a tin tub until I was 3, my family had a television with three channels from Memphis, and we had a truck. My mother, as I got older, was determined I was to participate in activities held 12 miles away in a town of about 5,000 people. I was not totally isolated.

Not everyone was so fortunate. You could see this in simple ways, like when someone needed to visit the doctor in town. When my brother or I needed our tetanus booster or polio vaccine, my daddy would take us. Other children without transportation also depended on my daddy and his truck to take them to town for doctor visits and other “serious” errands. If we needed health care, we would all come to depend on anyone with transportation since there was no such thing as a transit system. It is the same way today in many areas, even with telemedicine.

I attended the school for the “country kids” from the first through sixth grades. Most of us rode a school bus, and on my 45-minute daily ride to school, I discovered how unfair the world was, and how mean children could be to those who were different. The “back of the bus” kids knew their place because they were shamed by comments made by others regarding hygiene and outward appearance. In the 1950s, schools in Arkansas were not racially integrated, so my first encounter with inequity was a close-up view of race-driven poverty and the crippling effect it had on the self-esteem and social development of many of my peers.

I made good grades in elementary school, and my third grade teacher rewarded me by giving me extra jobs like starting a school library and serving as a substitute teacher for my peers for two weeks. My good grades came to a screeching halt when I entered junior high school, when children from all over the district converged at one “city” school. The rigor of the curriculum and expectations of my previous small-town teachers were less than those in the city school, and it showed in the learning gaps I had to overcome. These learning gaps are still plaguing rural school children today as a result of myriad funding issues and federal, state, and local policies within public school systems.

During my third grade experience as a two-week substitute teacher, I realized I was destined to become a teacher. After a detour, I graduated college and returned home in the early 1970s as a first grade teacher in a rural school about 5 miles from my childhood home. In the middle of a cotton field, with no air conditioning in the classroom or trees for shade, where 100% of the children lived in poverty, I quickly realized that conditions had to change. After two years of teaching and working on my graduate degree, I received a grant to fund a summer kindergarten program for the community children. It was extremely successful, and the data we collected persuaded the school district to begin full-day kindergarten two years later.

The first grade children I taught in the Mississippi Delta in the mid 1970s lacked the benefit of an early childhood kindergarten experience, just like many children in Arkansas. Schools were under a court order to integrate, but it was clear the district was not interested nor was integration enforced. Of the 1,000 children in grades 1-6 in the school, 99.9% were African American and receiving free lunch. Given that we were a high-poverty, high-minority enrollment school, we got the “leftovers” and broken instructional equipment, as well as incomplete curriculum materials. We had the same materials as other elementary schools in the district, but the condition of the materials was not the same. With a cigar box and rubber bands as my speaker for the “reading machine,” I was expected to teach phonics.

The Importance of Defining Rurality and Counting Rural Kids

In 2020, thousands of children living in rural America experience the same challenges of isolationism, poverty, and family dysfunction that we did decades earlier. The differences are even greater because of the digital divide and resource gaps. Some students have limited or no access to technology, failing to expose them to a life outside the 10-mile radius of their home. Others may have broadband, if their families can afford it, but do they have the support needed to master their online lessons? In spite of technology, have they learned more? Has the introduction of technology actually broadened the learning gap? Some of the answers depend on resources, and resources depend on numbers, which can be a problem for rural communities.

The U.S. Census Bureau has defined rural as “all population, housing, and territory not included within an urbanized area or urban cluster” (Ratcliffe et. al, 2016). There are many classifications for rural, typically based on population density, urbanization, and daily commuting patterns. Defining rural is important because population counts, determined by the Census, are tied to the amount of funding allocated by various federal programs serving children and families, the flexibility of how funds may be spent, and representative voice in Congress. Formulas for funding of local education agencies and basic needs are determined by the Census count, including funding of programs such as Head Start, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), free- or reduced-priced school lunches for low-income children, teacher training programs, as well as infrastructure programs such as roads and bridges (America Counts, 2020). The historical undercounting of rural children continues to negatively impact the allocation of funds for these children.

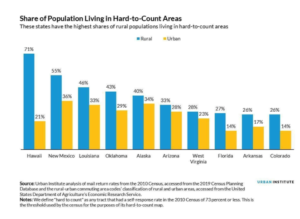

Reports such as The Undercount of Young Children, released by the Census Bureau in 2014, and the American Community Survey detail how the undercounting of children, especially those birth through 4-years old, negatively impacts rural communities (U.S. Department of Commerce, 2014). According to the Urban Institute, in 21 states the share of the rural population living in hard-to-count areas exceeds the share of the urban population living in hard-to-count areas. In rural areas in New Mexico and Louisiana, for example, approximately half of residents live in a hard-to-count census tract. In rural Hawaii, that share is nearly three-quarters (Gold & Su, 2019).

Various theories are offered as to the lack of participation in rural areas. Common reasons include that many residents use post office boxes rather than physical addresses for mail delivery, making it difficult for enumerators to locate residents; residents fear sharing personal information with the government; and families lack access to complete the Census data online. COVID-19 has exacerbated problems because it is difficult for the U.S. Census Office to secure and keep enumerators employed in isolated areas. The process of collecting data in 2020 is more dependent on technology and connectivity than in 2010, resulting in further problems collecting and recording data. Historically, many of these problems have been noted and reported to the Census Bureau, which lists pre-COVID-19 rural count strategies on their website (America Counts, 2020).

Understanding the Impact and Reality of COVID on Rural Child Care Providers

The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the painful extent of inequities in rural America, which have not gone away over the last many decades for young children and the people who take care of them. When early care and education professionals in Mississippi were surveyed in the summer of 2020 by the Graduate Center for the Study of Early Learning at the University of Mississippi and through a focus group of rural early childhood educators organized by the National Association for the Education of Young Children, these professionals identified their greatest needs during this time. Their needs included access to supplies, the ability to purchase essential food items, financial and policy support for existing programs, prioritizing child care needs including service to essential workers, and the creation of a grant/loan program during this time of crisis. The pain experienced by rural child care workers comes through in their survey responses, some of which are shared below.

While the pandemic impacted the income of all Americans, the case can be made that families in rural areas were hit harder than others. In 2016, the U.S. Census Bureau issued a report comparing the income differences between urban and rural areas of the country. Looking at all four regions of the country, poverty rates were consistently lower for those living in rural areas than for those living in urban areas, with the largest differences in the Midwest and Northeast (Bishaw & Posey, 2016). With lower incomes due to numerous factors, including a profound difference in the minimum wage between states and an extremely low federally required minimum wage, rural families are financially compromised based on their zip code.

The experiences and stories shared by these professionals describe the need, desperation, uncertainty, and fear of small program owners in small towns and rural areas. There is fear for one’s own health, the health of family members at-risk due to compromised immune systems, fear of spreading COVID among the children served and their families. There is fear of an insufficient amount of food to feed the children, fear of a lack of supplies and an inability to obtain the basics.

One professional shared: “Arkansas Department of Health suggested masks for child care workers, but we can’t find them and don’t have the extra funding for them anyway. The owner’s down to one can of disinfectant. Relatives and others are making multiple trips to stores. She’s written letters to all the local grocery stores, chamber of commerce, etc. but no help.”

Another child care provider described a different but related concern: “To be honest, I did not know what to do. Do I stay open and be a nervous wreck worried I’d disinfected enough. Worried the kids could become sick, thus making me and my husband sick. Babies don’t social distance, we are family and it’s just not possible. I prayed about what to do and after talking to my daycare families, decided it would be best to shut down.”

Financial fear is a great concern. In addition to the fear of loss of income, fears of letting employees and families down and of having to close looms in many instances. One program owner said, “If our enrollment doesn’t grow after this runs out, we will have to reduce hours and/or send staff home AND put classrooms together. I have single parents and widows on staff who can’t make it work on four hours a day.”

Another shared, “Our current bank account is at $40.00. 90% of our budget is salary. As soon as our income comes in, it goes right out the door through payment to employees. We get tuition one week and spend it on payroll the next.”

Providers note that the waiting time for funds that have been allocated are unreasonable. “There are funds that have been given for supplies, for masks, and basic PPE for childcare, but we are still waiting,” one owner shared.

Many professional early childhood teachers and caregivers struggle as they work to serve others. One program owner wrote, “Since this started we have families in need, we are only charging them half tuition. All of this to say we’re basically paying to stay open. I don’t know how long we can do that, of course, it’s not sustainable. We have a business loan, payroll, utilities, of course food, as you’re well aware, etc.–seems out of place still going with no income.” Another shares similar feelings and needs, “Some financial help would have been so appreciated since I had to close. Child care is my chosen profession.”

Providers described cycles of personal frustration and system failure. One child care worker shared, “After this [pandemic] happened I have applied for the Emergency Disaster Loan with no reply, nearly a month after my initial application. I applied for unemployment only to be told that money isn’t available for self-employed people yet. I have applied for and been turned down for the Payroll Protection Program loan because I pay my help using a 1099, I don’t meet the guidelines for assistance. As my bank account depletes, I am forced into applying for SNAP benefits which I would be very relieved if only I knew I could feed my family but that has been a dead end too. It’s been nearly 2 weeks since I placed that application and I called to follow up a few days ago and I was told they haven’t even received my online application yet because their system is so backed up. I have not received a stimulus check because I don’t get a refund therefore mine will have to be mailed and currently, I cannot track that process either. I have zero money coming in and no sign of when help will arrive.”

Survey responses made clear providers’ fear and desperation, as shown in this workers’ plea for support: “There was money to be had, then they ran out leaving my small operation to fall even deeper in the crack of despair. I need to return to work for my families and by work, I mean living. I have no job, no money and no way to live. Please, Please, Please!!! I need HELP. Thank you to whomever reads this letter. God Bless you for anything you will be able to help.”

Rural America Needs Our Help

How much longer can we gamble with the lives of children and families? America can’t wait until another medical pandemic hits or the next natural disaster occurs to change its policies and address inequities for young children and their providers in rural communities. We can’t expect small towns and small programs to continue to serve the rural communities, parents, and children with limited support. “Equity” and “equality” are terms decision-makers and system implementers have confused since before Brown v. Board of Education and the civil rights movement. As educators who taught in high-poverty schools in the Mississippi and Arkansas Delta in the 1970’s under “the separate but equal” administrative mindset, it is sad to see so little progress in moving the conversation from equal to equitable systems. We know how and what to do, but do we have the political will?

References

America Counts. (2020, July). Counting People in Rural and Remote Places. United States Census Bureau. Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2020/07/2020-census-will-help-school-districts-prepare-for-next-generation-of-students.html

Bishaw, A. & Posey, K. (2016). A Comparison of Rural and Urban America: Household Income and Poverty. United States Census Bureau. Retrieved on August 2, 2020 from https://www.census.gov/newsroom/blogs/random-samplings/2016/12/a_comparison_of_rura.html

Gold A. & Su, Y. (2019, October 31). Rural Communities Aren’t Immune from a Census Undercount. Here’s How They Can Prepare for 2020. Urban Institute. Retrieved on August 22, 2020 from https://www.urban.org/urban-wire/rural-communities-arent-immune-census-undercount-heres-how-they-can-prepare-2020

Ratcliffe, M., Burd, C., Holder. K., & Fields, A. (2016). Defining Rural at the U.S. Census Bureau: American Community Survey and Geography Brief. United States Census Bureau. Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2016/acs/acsgeo-1.pdf.

U.S. Department of Commerce. (2014, February). The Undercount of Young Children. United States Census Bureau. Retrieved on August 21, 2020 from https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/working-papers/2014/demo/2014-undercount-children.pdf