English Learners (ELs) are the fastest growing population of public school students in the US. Close to 6 million ELs are enrolled in public schools, an increase of more than 100 percent since 1911. MAEC has a proven record of providing support to address the needs for ELs. Our services include conducting needs assessments, goal setting in collaboration with clients, technical assistance, training, coaching, and project evaluation. Our staff provides research-based approaches to improve the overall educational outcomes for ELs.

Community Resource Mapping – English Learners

MAEC uses a strengths-based approach for asset mapping, since often the best solutions come from within the communities in which our districts/schools reside. These key stakeholders include districts, schools, communities, and families all who are seeking to increase student achievement. To this end, MAEC conducts community walks and community resource mapping to identify potential partners and allies for effective and efficient delivery of services. This process includes attention to alignment between district and school needs and priorities so together partners can build the social and human capital that will help students and staff thrive.

Comprehensive Needs Assessment – English Learners

Beginning with a disaggregated data analysis of student achievement, student discipline, and school climate, MAEC is able to effectively determine client strengths and areas of need. This collaborative inquiry approach enables MAEC to examine multiple sources of data. Using a culturally responsive and equity framework, further creates opportunities to develop operational action plans to tackle complex challenges that pose barriers to gains in student achievement.

Culturally Responsive Family, School, and Community Engagement – English Learners

A family is a child’s first teacher. When families’ partner with schools and community organizations, children thrive. To produce the best results for students, MAEC builds the capacity of families, educators, schools, and community organizations to collaborate, exchange ideas, and develop and implement policies and action plans. We build on the collaborative strengths of families, educators, and community members so they can each contribute to the development and success of diverse students.

Culturally Responsive Leadership – English Learners

Leaders set the tone and expectations of any organization. They do this by responding effectively to the diverse communities that they serve, being asset-focused, and proactive problem solvers. Culturally responsive leadership technical assistance provides a multi-dimensional framework that builds capacity of educators who are culturally informed and highly skilled in culturally responsive practice.

Culturally Responsive Pedagogy – English Learners

Culturally responsive pedagogy is a method and practice of teaching in which educators and providers build on the assets that their students and families bring into the classroom. As the populations of our students grow more diverse, staff must be better prepared to respond to their needs. This requires a greater understanding and knowledge of their students’ culture, strengths, and socio-political contexts. With this practice, schools can become hubs of learning focused on the well being of the students and families being served.

Policy & Procedural Reviews – English Learners

In educational systems, policies and procedures often inform practice. However, some policies or procedures may have unintended consequences when implemented that serve to further silo organizational efforts to close opportunity gaps. To address this challenge, MAEC provides state departments, districts, schools, and organizations with policy and procedural reviews to ensure they are equitable, effective, and comply with federal, state, and local laws and regulations.

Ensuring Educational Equity for English Learners

Under Title VI and Title III of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, school districts are prohibited from discriminating on the basis of race, color, and national origin. This training highlights the requirements regarding the provision of services for ELs with an emphasis on the identification, placement, provision of alternative programs for ELs, access to challenging content, and assessment. Legal rights of parents/guardians are also included as part of MAC’s training.

Navigating the School System for Families of English Learners

This training helps build the capacity of parent involvement coordinators, Title I & Title III specialists, and community leaders to effectively engage families of English Learners in their children’s education. The training focuses on: (1) Creating welcoming schools and classrooms; (2) Considerations for engagement of immigrant families; (3) Linking family engagement to learning; and (4) Models for effectively engaging EL families in their children’s education.

Working Effectively with English Learners

This training helps build the capacity of administrators and staff to design and implement effective programs to meet the needs of English Learners. MAC’s training highlights the cultural context of English Learners, the levels of English proficiency needed for academic success, how to effectively teach Common Core and/or challenging content to ELs, and strategies for creating inclusive schools and classrooms.

Office of the State Superintendent of Education

MAEC partners with the Office of the State Superintendent of Education (OSSE) for the District of Columbia to ensure that English Learners gain academic and language proficiency to prepare them to be global leaders. MAEC staff sits on the Title III Advisory Council and provides the following technical assistance:

- Development of an adapted monitoring tool to assess Local Educational Agencies (LEAs) services to English Learners;

- Analysis of initial monitoring results and revised action plans to support LEAs in the delivery of EL services; and

- Provide key findings and recommendations based on the results of monitoring.

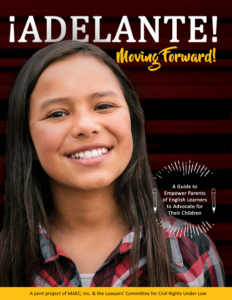

¡Adelante! Moving Forward!

¡Adelante! Moving Forward!

A Guide to Empower Parents of English Learners to Advocate for their Children

In 2010, approximately five million students in the United States were identified as English Learners (ELs). Students under this category have different English proficiency levels and years of formal education. Schools must be able to support students of different backgrounds and proficiency levels equally and ensure access to quality education for academic success as they continue to learn English.

There is a substantial body of legislation, the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA), which protects the rights of these students. Unfortunately, many families of ELs are unaware of these laws and thus cannot advocate for their children. ¡Adelante! Moving Forward! A Guide to Empower Parents of English Learners to Advocate for their Children is designed as an informational training tool to provide trainers of immigrant families and family leaders with user-friendly and accessible information regarding the legal responsibilities of educational agencies serving ELs and the rights of families of ELs.

The publication was developed through a partnership between the MAEC and the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law’s Parental Readiness and Empowerment Program (PREP). It is available in English and Spanish.

In 2010, approximately five million students in the United States were identified as English Learners (ELs). Students under this category have different English proficiency levels and years of formal education. Schools must be able to support students of different backgrounds and proficiency levels equally and ensure access to quality education for academic success as they continue to learn English.

There is a substantial body of legislation, the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA), which protects the rights of these students. Unfortunately, many families of ELs are unaware of these laws and thus cannot advocate for their children. ¡Adelante! Moving Forward! A Guide to Empower Parents of English Learners to Advocate for their Children is designed as an informational training tool to provide trainers of immigrant families and family leaders with user-friendly and accessible information regarding the legal responsibilities of educational agencies serving ELs and the rights of families of ELs.

The publication was developed through a partnership between the MAEC and the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law’s Parental Readiness and Empowerment Program (PREP). It is available in English and Spanish.

Bio-Social-Emotional Needs of Immigrant Students, with a Focus on Central Americans

Bio-Social-Emotional Needs of Immigrant Students, with a Focus on Central Americans

Part of CEE’s Exploring Equity Issues series, this paper discusses social and emotional learning (SEL) and the special challenges faced by immigrant students in this area. For immigrant students, the challenge of SEL is compounded by their simultaneous navigation of social and academic displacement, trauma, and family reunification. The paper concludes with both school-wide and teacher strategies that respond to immigrant student needs.

Bio-Social-Emotional Needs of Immigrant Students, with a Focus on Central Americans

PART I: BACKGROUND

Social and emotional learning (SEL) is the process by which individuals learn to understand and manage their emotions, maintain positive relationships, and make responsible decisions. For immigrant students, this process holds additional challenges, as they learn these skills while also navigating complex emotional reactions to social and academic displacement, trauma, and family reunification. “I am from El Salvador. My uncle, brother and I decided to come to the U.S. because the gangs were threatening us. One of my friends was killed. On the way here we were kidnapped in Mexico and held for three months until a ransom was sent. There was another man with us who had all five of his fingers on one hand cut off by the kidnappers, and then they stabbed him to death right in front of my brother and I. Once we got to the border, we were caught by ICE and my uncle was sent back home. I saw a counselor when I first got here, and now I don’t have nightmares anymore.” HISTORY OF IMMIGRATION AND CURRENT TRENDS Immigration to the United States from Central America has long been driven by economic difficulties and violence. In the last four decades, these countries have experienced civil wars, crippling poverty, increased gang violence and narco-trafficking, and disintegration of civil structures. According to World Atlas statistics, since 2014 El Salvador and Honduras have been named as countries with the highest murder rates that are not at war. Children are either targeted for recruitment into an expansive network of gang activity or are living under their threat. Consequently, the flow of children entering the United States has increased as they seek safety. These children do not have refugee status, but rather must independently find and fund legal counsel. Without such assistance, they risk being deported to the countries they fled. From the years 2013-2015, the Migration Policy Institute reported a spike in Central American unaccompanied minors crossing the Mexican border into the United States, totaling 77,000 during this period. High Point High School in Prince George’s County, Maryland, currently has the largest numbers of ESOL students in the state. The total 2017-2018 ESOL enrollment thus far has topped 1,200 students. With increased anxiety over changing immigration policies, ESOL students are withdrawing or transferring to other schools at unseen rates; over 400 ESOL students have withdrawn from High Point this academic year. Students report that they are receiving deportation and voluntary departure notices, are re-locating to more affordable housing, or are choosing to work in order to prepare for a return to their home country, in spite of the safety risks. BIO-SOCIAL-EMOTIONAL NEEDS Newcomer immigrant students place particular demands on school staff, not only for specialized instructional interventions, but for social and mental health supports as well. Improving instruction requires awareness of intercultural communication and appropriate responses to students exposed to trauma, family loss, uncertain legal future, and cultural adjustment. Immigrant children are more likely to face numerous risks to healthy development (Close & Solberg, 2008). Biological needs to consider include access to health care and immunizations, interruption of eating/sleeping patterns, pre-existing health conditions, and the impact of chronic stress and trauma on the body. Limited exposure to sun and physical exercise also take their toll on newcomer immigrants from countries where most of their daily life took place outdoors. Social needs for belonging within their academic community cannot be overstated. A study of Latino students in the United States confirmed that students who felt more connected with their teachers and their school were also more motivated to attend school, which was in turn associated with better achievement (Close and Solberg, 2008). Newcomer students need opportunities to build relationships with their new peers, experience success in their new language and school, and begin the long task of attachment at home with biological parents or caretakers who may be virtual strangers. Newcomer students also need assistance with acculturation and orientation regarding school procedures, U.S. education norms, legal requirements such as attendance and immunization, and community resource information on low-cost health care and legal services. The students need an opportunity to understand that their culture shock, adjustment, and challenging relationships with unfamiliar family members in the context of time – that their current emotional state, be it stress, depression or anger, is temporary. In 2016, High Point conducted an anonymous survey of 294 newcomer students from Central America to help understand the scope of their social-emotional needs. Responses revealed that 52% had experienced gang/community violence in their home countries or on their journey to the United States, 35% had interrupted education, 45% had a loved one die in the previous year, 37% reported experiencing insomnia or nightmares regularly, and 79% reported a need for legal counseling. As trauma research has documented, children who have experienced trauma, fear, separation from family, and isolation are subject to a variety of psychological stressors and mental health challenges. Studies have shown some develop anxiety, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), or other conditions. Once in the United States, these students continue to worry about family members and friends who remain in their country; family members become ill, friends are murdered, relatives disappear. Trauma can cause interrupted sleep, poor concentration, anger/aggression, physical pain and/or social withdrawal. Trauma also can interfere with attention, memory, and cognition – all skills that are fundamental in learning.PART II: WHAT CAN WE DO?

SCHOOL-WIDE INTERVENTIONS Provide staff training on behaviors to watch for. School-wide interventions begin with training staff so educators are familiar with the geo-political causes of immigration, and the impacts of trauma. Staff training is necessary in order to understand and interpret behaviors a student may exhibit during their adjustment period – be it silence, disorganization, or disengagement. Provide immigrant students with specialized orientation. School staff can also provide a sense of safety to students and facilitate mastery of their new surroundings through teaching expectations and routines with visual reminders, supporting a culture of respect, and correcting with warm firmness. Bilingual orientation guides help with the task of mastery. These guides may include: a map of the school; information on community resources; important staff to know; websites and apps that can support English language learning; school procedures regarding code of conduct, absences, library use, and inclement weather policies; tips for managing culture shock; and strategies for building trust with new family members. Bilingual social work and family support staff are vital. School staff must also help newcomer students be aware of gang activity. Unaccompanied minors in particular are at an increased risk for recruitment either at school or in their communities. Students need to know the methods for recruitment (intimidation, skipping parties, drug trafficking), refusal techniques, and school staff who can support them. TEACHER INTERVENTIONS As teachers, we can draw on the research and interventions for trauma-informed and trauma-sensitive learning environments to respond to immigrant student needs. Marlene Wong of the Support for Students Exposed to Trauma program has designed school-based curriculum to support school-wide understanding and interventions to mitigate the impact of past trauma. All the best instructional techniques we have will depend on the student’s availability to engage with and learn from us. This need to belong has long been recognized as one of the most important psychological needs in humans (Maslow, 1943). Hence, our most essential tool in engaging with all youth, especially youth with traumatic histories, is ourselves – our warm, caring, dependable, steady, relational, limit-setting selves. As educators and support staff, we provide this necessary positive mirroring and a belief that students’ resilience is stronger than their challenges. Use mindfulness techniques in the classroom. Resiliency and post-trauma growth research emphasizes the need for students to learn emotional regulation, how to relate positively to others, and how to reason through challenges. Mindfulness techniques and grounding exercises can help students by teaching an awareness of their body and their mind in the present moment. Using five minutes of class on a routine bases for check-ins related to self-awareness (emotional state, physical and cognitive energy), deep breathing techniques, guided meditation, and simple movements to stimulate or calm the brain are all skills that students can learn in order to regulate their mind and body. These exercises can change the energy of the student and the energy in the classroom. Engage in classroom community building. The circle process is another method for strengthening classroom community and enhancing self-efficacy. Using one or two prompts and inviting students to respond provides an opportunity to build connections and normalize their experiences of adjustment. In addition, invite older student leaders who have lived through similar experiences, to share their challenges and successes with newcomer students. Given the changes in immigration policies specifically towards Central American students and families, we are likely to see an increase in anxiety-related and depressive behaviors. This could be manifested by poor attendance, self-harm and suicidal ideation, increased drug use, and dropping out of school. As caring educators, we need to know the daily realities of our students and how we can best address their needs, to support what they most desire – a safe and better life for themselves and their families.RESOURCES

- Helping Traumatized Children Learn

- National Child Traumatic Stress Network

- Niroga

- BRYCS: Refugee Children in U.S. Schools: A Toolkit for Teachers and School Personnel

REFERENCES

Blaustein, M., & Kinniburgh, K. M. (2010). Treating traumatic stress in children and adolescents: How to foster resilience through attachment, self-regulation, and competency. New York: Guilford Press. Boyes-Watson, C., & Pranis, K. (2015). Circle forward: Building a restorative school community. St. Paul, MN: Living Justice Press. Close, W., & Solberg, S. (2008). Predicting achievement, distress, and retention among lower-income Latino youth. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 72(1), 31-42. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2007.08.007 Eccles, J. S., & Roeser, R. W. (2011). Schools as Developmental Contexts During Adolescence. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 21(1), 225-241. doi:10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00725.x Maslow A. H. (1943). A theory of human motivation. Psychol. Rev., 50 370–396. \10.1037/h0054346 National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance (NCEE) home: Part of the U.S. Department of Education (ED). (n.d.). Retrieved March 21, 2018, from https://ies.ed.gov/ncee/edlabs/ Pariona, A. (2016, September 28). Murder Rate By Country. Retrieved March 21, 2018, from https://www.worldatlas.com/articles/murder-rates-by-country.html What is SEL? (n.d.). Retrieved March 21, 2018, from https://casel.org/what-is-sel/

Creating New Futures for Newcomers

Creating New Futures for Newcomers

Lessons from Five Schools that Serve K-12 Immigrants, Refugees, and Asylees Given the influx of immigrants and refugees over the past several years, newcomer students are found in the classrooms of small towns, suburbs, and big cities across the country and they bring with them a world of culturally diverse experiences and knowledge. Newcomers face myriad challenges to adapt and succeed in their new home and schools. They must learn how to navigate a new culture socially, master a new language, and adjust to a new, and typically different, educational system. Many of these students enter our schools with little or no formal education or fluency in English. Some have fled terrible conditions in their homelands. Others are here without their families. Despite these challenges, all share dreams of being successful students and productive members in our communities, while remaining linked to their cultures and native languages as they become first generation Americans. To help make these dreams come true, we searched for “bright spots,” schools that offer promising and effective strategies for newcomers in K-12 classrooms. In this report, we focus on five very different schools that serve newcomers, each offering promising strategies, proven approaches, and fresh ideas that can benefit all educators, but especially those who work with immigrant and refugee students. We discuss curriculum and instruction, professional learning, school orientation, social-emotional and health support, and ways to partner with newcomer families and communities. We learn how newcomer schools assist students to adjust and thrive. This report was developed through a partnership between MAEC and WestEd. The main author is BethAnn Berliner, Senior Researcher/Project Director at WestEd. Click here for more information and to download the publication.

Engaging Immigrant and English Learner Families in their Children’s Learning

Engaging Immigrant and English Learner Families in their Children’s Learning

While the benefits of family engagement are well known, reaching immigrant parents and caretakers present many challenges – from both sides: educators and immigrants.

Engaging Immigrant and English Learner Families in their Children’s Learning

PART I: THE LONG ROAD TRAVELED

Last month, Exploring Equity Issues focused on the multiple obstacles that immigrant students face adjusting to their new lives in the United States. This month we address their families, specifically, engaging them in their children’s learning. While the benefits of family engagement are well known, reaching immigrant parents and caretakers present many challenges – from both sides: educators and immigrants. Why is it important to engage immigrant and English Learner (EL) families? According to the 2016 Current Population Survey, immigrants and their U.S.-born children now number approximately 84.3 million people, or 27 percent of the overall U.S. population. In 2015, English Learners (ELs) ages 5 and older represented nine percent of the U.S. student population (Migration Policy Institute, 2017). A QUICK RECAP ON FAMILY ENGAGEMENT More than 50 years of research indicate that family engagement plays a critical role in supporting children’s learning, encouraging grit, determination, and will to succeed. Moreover, findings show that when families are involved, children improve in a range of areas: better grades, higher scores on achievement tests, lower drop-out rates, regular school attendance, better social skills, improved behavior, leading to better chances students will graduate from high school and continue their education (Henderson & Mapp, 2202; Smith, Stern, & Shatrova, 2008; Hayes, 2012; Shute et al., 2011; Fan & Chen, 2001). YES, BUT WHO GETS INVOLVED? Results of the study Parent and Family Involvement in Education from the National Household Education Surveys Program of 2012, show that Latino and Asian parents are less likely to attend school or class events or volunteer or serve on school committees (National Center for Education Statistics, 2016). While 82 percent of White parents attended school-related events, only 64 percent of Latino parents and Asian parents participated. The same differences can be found in volunteering on school committees. Fifty percent of White parents participated in contrast with 32 percent of Latino parents and 37 percent of Asian parents. The same study also shows differences in parent and caregiver participation when English spoken at home is taken into consideration. Families who speak English at home tend to participate more in schools compared with those who do not. Data indicate that in households where both parents speak English at home, 78 percent participate in class events compared to 62 percent if only one parent speaks English and 50 percent if no parent speaks English. Immigrant families face many barriers as they try to become informed or involved in their child’s school. These barriers, which include limited English proficiency, unfamiliarity with the school system, and differences in cultural norms, can limit communication and participation in schools. Given the increasing number of immigrant families and their relative low levels of engagement with schools, educators should consider the following approaches to promote engagement. It begins with acknowledging and changing some preconceptions. CHANGING MINDSETS Switch to an asset-based approach to immigrant families and their children. Deficit-thinking treats students’ and families’ cultural, language, and socioeconomic characteristics as causes of students’ low academic achievement. Teachers with this perspective perceive immigrant students and their parents as a heavy load that needs to be lifted and assimilated into American society in order to succeed. Research studies have shown, however, that an asset-based model recognizes that the funds of knowledge immigrant families bring to school – including their language – provide a solid foundation for positive and effective interaction between school and families and nurture students’ self-esteem and academic achievement (Gonzalez, Moll, & Amanti, 2005; Bruton & Robles-Piña, 2009). Acknowledge that immigrant and EL families are interested in their children’s educational success. Many schools interpret the low level of engagement as a sign of immigrant and EL families’ lack of interest in promoting educational success. Research indicates that the majority of families, regardless of race, ethnicity, or socioeconomic status, are interested in their children’s educational achievement (Chavkin & Williams, 1993; Henderson & Mapp, 2002). The myth that immigrants do not value education is based on a deficit model that claims they do not have the knowledge or cultural capital to provide their children with high aspirations and a positive attitude (Moreno & Valencia, 2002; Olivos & Mendoza, 2010). This myth has been debunked by research studies and legal actions that document that immigrant families have high expectations for their children’s educational attainments (Gonzalez, Moll & Amanti, 2005; Orozco, 2008). Immigrant families have actively participated to improve the education of their children, including historical litigation cases, advocacy organizations, individual activities, and political demonstrations/legislation where parents and caretakers struggled and advocated for them (Moreno & Valencia, 2002). Recognize that immigrant and EL families have different cultural expectations. Many immigrants come from countries where parents and caretakers are not expected to participate actively in school-related activities. In addition, immigrants face different cultural expectations from teachers and schools (Kao et al., 2013). In other countries, students are expected to learn largely from their teachers. In the United States, however, families are expected to actively engage with the schools in a joint effort to educate their children. In order to address this issue, schools need to acknowledge this fact and develop strategies to inform families about the impact of family engagement and their role in advocating for their children. Con Respeto (Respectfully) - Develop Two-Way Partnerships. Several research studies show that the ways in which schools engage families influences why and how parents participate in their children’s education. A welcoming, honoring, culturally-responsive and positive school environment creates conditions for parents of culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds to participate (Mapp, 2003). The findings of the ethnographic studies of Guadalupe Valdez (1996) marked the beginning of an approach that attempted to change how schools worked with immigrant families. Initiatives to engage immigrants needs to use an approach where parents are seen as equal partners in two-way partnerships rather than passive participants that are invited to follow school-initiated activities.PART II: WHAT CAN WE DO – SPECIFICALLY?

In addition to changing the way immigrant and EL families are perceived and developing two-way partnerships, schools engage and sustain the participation of families of linguistically and culturally diverse backgrounds using the strategies described below: LEARN ABOUT YOUR EL POPULATION The first step in any relationship is to learn about each other. What languages do your immigrant and EL families speak? What countries do they come from? How many of your ELs are migrants, refugees? How many were born in the U.S.? Address these questions in a personal way – not through impersonal surveys. Help your immigrant families see you are interested in them. Parents and caretakers appreciate face-to-face communications. If they have trouble coming into the school – because they have work commitments, transportation challenges, or other reasons – try making phone calls. CREATE A WELCOMING ENVIRONMENT Provide families with information and/or materials in their home language. This should include even informal notices. Post signs in different languages. Establish a family room or bulletin board that highlights their cultures and languages. Embrace their cultures and funds of knowledge as assets for the school curriculum and overall school culture. HIRE FAMILY LIAISONS THAT SPEAK THE MOST COMMONLY USED LANGUAGE(S) IN YOUR EL COMMUNITY When budgets allow, hire school staff who speak the most commonly used languages. Reach out to bilingual parents to help bridge these gaps. Use family-to-family connections at the school and community level. OFFER TRAINING TO YOUR IMMIGRANT AND EL FAMILIES Help your families understand the U.S. public education system. Provide instructions in conversational terms, defining technical jargon clearly (or avoiding it altogether). Teach them how to advocate for their children. Provide family literacy and/or ESL classes. Remember to schedule activities at times when they can attend. Provide child care and interpreters if needed. SUPPORT FAMILIES TO SUCCESSFULLY ENGAGE IN THEIR CHILDREN'S LEARNING Immigrant and EL families may feel they cannot help with their children’s learning because they do not understand English. Reassure them that they can help their children in school even when they do not understand the language. Immigrant and EL families can begin with the same strategies that apply to all families: provide a place where their child can do homework; check that their child completes homework each night; and ask their child to tell them about what he or she learned in school during the day. Then suggest that they read and tell stories in their native language. Engaging immigrant and EL families is crucial to addressing the demands children face as they live and achieve in the U.S. Providing a welcoming, inclusive, and respectful environment to families in our schools helps ensure they are able to offer the support their children need to succeed. Written by Maria del Rosario (Charo) Basterra and Phoebe Schlanger, MAEC.REFERENCES

Bruton, A. & Robles-Piña, R. (2009). Deficit Thinking and Hispanic Student Achievement: Scientific Information Resources. Problems of Education in the 21st Century, 15, 41-48. Chavkin, N. & Williams, D. (1993). Minority Parents and the Elementary School: Attitudes and Practices. In N. Chavkin (Ed.), Families and Schools in a Pluralistic Society (pp. 72-83), Albany: State University of New York Press. Gonzalez, N., Moll, L., & Amanti, C. (2005). Funds of Knowledge: Theorizing Practices in Household Communities, and Classrooms. Mahwah, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Fan, X., X, & Chen, M. (2001). Parental Involvement and Students’ Academic Achievement: A Meta-Analyisis. Educational Psychology Review, 13 (1), 1-22. Hayes, D. (2012). Parental Involvement and Achievement Outcomes in African American Adolescents. Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 43(3), 567-582. Henderson, A. & Mapp, K. (2002). A New Wave of Evidence: The Impact of School, Family, and Community Connections on Student Achievement. Austin, TX: Southwest Educational Development Laboratory. Kao, G., Vaquera, E., & Goyette, K. (2013). Education & Immigration. Polity Press, Malden, MA. Mapp, K. (2003). Having Their Say: Parents Describe Why and How They Are Engaged in Their Children's Learning. School Community Journal, v13 n1 p35-64. Migration Policy Institute (2017). Frequently Requested Statistics on Immigrants and Immigration in the United States. Moreno, R. & Valencia, R. (2002). Chicano Families and Schools: Myths, Knowledge, and Future Directions for Understanding. In R. Valencia (Ed.), Chicano school failure and success. New York: Falmer Press. National Center for Education Statistics (2016). Parent and Family Involvement in Education, from the National Household Education Surveys Program of 2012. US Department of Education. Olivos, E. & Mendoza, M. (2010). Immigration and Educational Inequality: Examining Latino Immigrant Parent’s En-gagement in US Public Schools. Journal of Immigrant & Refugee Studies, 8(3)m 339-357. Shute, S., Underwood, J., Razzourk, R. (2011). A Review of the Relationship Between Parental Involvement and Secondary School Students’ Academic Achievement. Educational Research International. Smith, J., Stern, K., & Shatrova, Z. (2008). Factors Inhibiting Hispanic Parents’ School Involvement. Rural Education, 29(2), 8-13. Valdez, G. (1996). Con Respeto. Bridging the Distances Between Culturally Diverse Families and Schools. An Ethno-graphic Portrait. Teachers College Press Download: Exploring Equity - Engaging Immigrant Parents in Children's Education

Promoting a Safe and Welcoming Environment for Immigrant Students

Promoting a Safe and Welcoming Environment for Immigrant Students

Part of CEE's Exploring Equity Issues series, this paper gives a background on the challenges faced by immigrant and EL students in public schools and provides strategies on what schools can do to make their schools more welcoming.

¡Adelante! Moving Forward!

¡Adelante! Moving Forward!  Bio-Social-Emotional Needs of Immigrant Students, with a Focus on Central Americans

Bio-Social-Emotional Needs of Immigrant Students, with a Focus on Central Americans